For decades, antibiotics have been seen as a quick fix in shrimp farming. Yet at FARM 2025 in Jakarta, Dr. Heny Budi Utari, researcher at Central Proteina Prima, reminded that what seems like an easy solution comes with hidden costs. She urged farmers, industry leaders, and regulators to reconsider their approach before the problem spirals out of control.

Dr. Heny began by acknowledging a truth many farmers already know. Antibiotics are cheap, easy to use, and appear effective when disease strikes. But she explained that this reliance has become a trap. In recent years, residues of antibiotics have been detected in exported shrimp, leading to rejection in some of Indonesia’s most important markets. Products from India, Vietnam, and China have faced similar scrutiny, but Indonesia cannot afford to fall into the same cycle. Every shipment that is refused damages not only a company but the reputation of the nation’s shrimp sector.

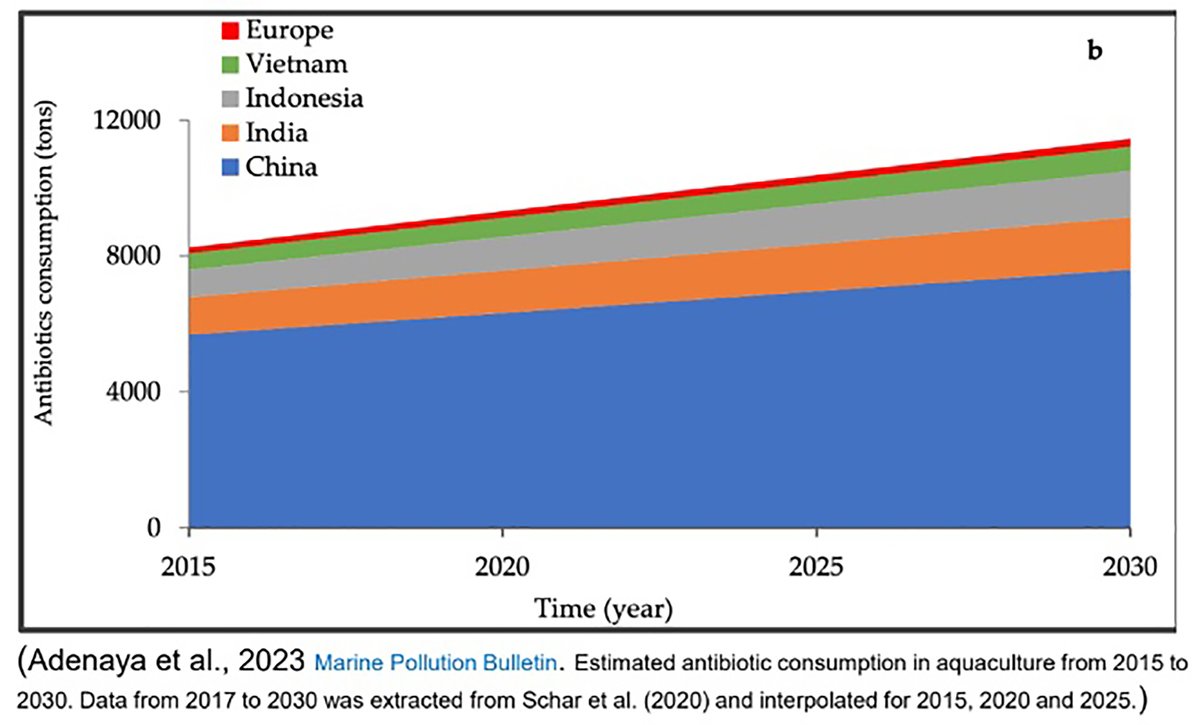

Figure 1. Antibiotic use in the aquaculture industry in several countries. Credits: Dr. Heny Budi Utari

The most dangerous impact is antimicrobial resistance. Bacteria are living organisms, and when exposed to antibiotics repeatedly, they adapt. Over time, they learn to survive. This means that antibiotics that once worked no longer have the same effect. What begins in a pond can move into the food chain, ultimately threatening human health. Dr. Heny warned that antimicrobial resistance is not a theoretical risk. It is already happening. In fact, cases of shrimp containing residues of nitrofuran and chloramphenicol have been recorded in shipments from Indonesia in 2024, including sulfites, and both May and June 2025.

She highlighted another issue that has compounded the problem. Some farmers misuse antibiotics to treat conditions for which they were never intended. Viral infections, for example, cannot be cured with antibiotics. Yet antibiotics are still applied as though they are a universal remedy. Dr. Heny described this as treating a headache by curing the stomach. The result is not only ineffective but also creates antimicrobial resistance (AMR), posing a significant danger. It can act as a superbug, leaving behind residues in shrimp tissue that are difficult to overcome.

She pointed out that other countries are already tightening controls. Japan, the U.S, and the E.U. have grown stricter with testing. Once Indonesia gains a reputation for being careless, it becomes extremely difficult to regain trust. Negative campaigns from trade competitors amplify these weaknesses, putting added pressure on local farmers. For Dr. Heny, this is why antibiotics are not just a technical issue. They are a national issue that affects the global image of Indonesian shrimp.

Toward safer and sustainable practices

Despite painting a serious picture, Dr. Heny offered solutions. She emphasized that the future of shrimp farming lies not in combating disease with chemicals, but in preventing it from taking hold in the first place. Biosecurity, she said, must become the backbone of modern aquaculture. This means stricter hygiene at every step, from disinfecting trucks before they enter farm sites to ensuring broodstock are tested and free of pathogens before they are introduced.

She encouraged farmers to embrace probiotics and other natural alternatives. Unlike antibiotics, these do not leave behind harmful residues. Instead, they strengthen the shrimp’s natural defenses, making them more resilient to common pathogens. She noted that farms that have invested in probiotics and proper management have already shown promising results, proving that the industry does not need to rely on outdated practices.

Dr. Heny also emphasized the importance of empowering farmers through access to small-scale laboratories. With simple equipment, farms can conduct their own probiotic tests and identify threats before they spread. This approach reduces dependence on external laboratories and allows farmers to make faster, better-informed decisions. For her, building capacity at the grassroots level is essential because no single company or government agency can manage the problem alone.

Toward the end of her session, she appealed for collective discipline. One farmer’s decision to use banned antibiotics can jeopardize the entire industry. Export markets rarely distinguish between one producer and another. They judge by country of origin. That is why she called on farmers, companies, regulators, and researchers to act together. The industry must present a united front, ensuring that Indonesian shrimp is not only competitive in terms of price and volume but also trusted for its safety and quality.

She acknowledged that change is never easy, especially when antibiotics have been used for decades as the most straightforward answer to disease. Yet she argued that this very moment represents a turning point. The global market is increasingly demanding sustainable products, and countries that adapt quickly will thrive while those that cling to old practices will fall behind.

In closing, she reminded us that the decisions made today will shape the industry for generations (sustainable shrimp farming). Shrimp farming has brought prosperity to many regions in Indonesia, and it has the potential to do much more. But this promise will only be realized if the sector dares to move away from antibiotics and embrace healthier, safer, and more responsible alternatives.

Read more about FARM 2025:

FARM 2025: Building the future of shrimp together