With an estimated population of around 175.69 million in 2025, Bangladesh is the eighth most populous country in the world. They love to eat fish and it plays a crucial role in the Bangladeshi diet, providing more than 60% of animal-source protein. In 2000, per capita fish consumption was 24 grams per day, rising to 67.8 grams per day in 2023.

This growing population has driven a shift from capture fisheries to aquaculture to meet the increasing demand for fish and fulfill the nutritional needs of the large population. Of the approximately 5 million tons of total fish produced in 2022, 2.8 million tons came from aquaculture. Bangladesh currently ranks fifth among the world’s major aquaculture-producing countries. The government aims to further increase fish production, setting a target of 8.4 million tons by 2041. Since capture fisheries are not expected to grow, additional 5-6 million tons will need to come from aquaculture to meet that goal.

The country primarily farms freshwater fish, which accounts for 90% of total production, along with some shrimp. Domestic carp species and local minor catfish like Clarias sp. and Ompok pabda have traditionally been raised, but there is now a growing shift toward tilapia (the most produced species), pangasius, and various carp species (the most produced group).

Carp farming is not standardized, with practices varying widely across the country – some farmers use feed, others use fertilizers, and so on. However, tilapia farmers are generally more focused on profitability and nutrition, using floating feeds and more modernized practices.

At the USSEC Aqua Tech Talks held in Sri Lanka, Aquafeed.com spoke with Mahbub Alam Khan, aquaculture nutrition consultant at Solutions for Fisheries & Aquaculture (SoFA). He shared insights into the aquaculture industry in Bangladesh and discussed the challenges and opportunities facing the aquafeed sector as it works to support the country’s expanding aquaculture production.

Aquafeed production

Aquaculture in Bangladesh has evolved significantly, from extensive carp culture systems using farm-made moist feed in the 1970s, to more intensive systems with sinking pellets in the 1990s, and finally to commercial feeds in the 2000s.

“In the 2000s, production shifted to high stocking densities and the use of sinking feeds, which increased the risk of disease outbreaks due to water quality deterioration. In the 2010s, floating feeds, along with improved formulations, enabled greater growth in fish farming,” said Khan.

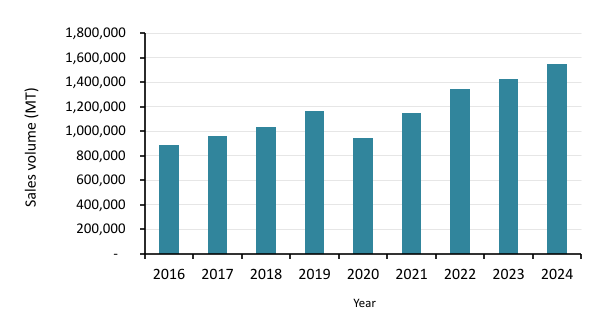

According to Khan, total fish feed production in the country has increased alongside aquaculture output, rising from 890,000 tons in 2016 to 1,546,318 tons in 2024 (Fig. 1). Of the 2024 total, 1,152,713 tons (74.55%) were floating feeds and 394,405 tons (25.5%) were sinking feeds.

Figure 1. Fish feed production in Bangladesh from 2016 to 2024. Source: Mahbub Alam Khan, personal communication.

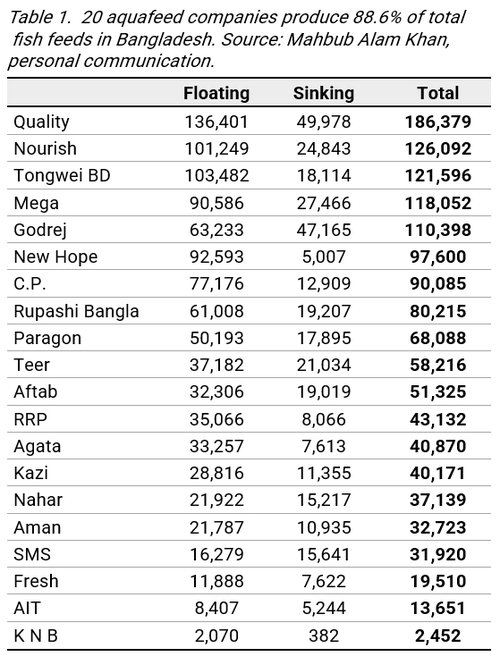

There are 43 companies producing aquafeed locally, including Bangladeshi firms and international companies such as China’s New Hope and Tongwei, and Thailand’s CP (Table 1). “Bangladeshi companies still lead in volume, but Chinese companies like Tongwei and New Hope, as well as CP, are gaining ground. CP also supplies high-quality tilapia fry,” Khan said.

Bangladeshi feed producers are losing market share due to issues with quality, cost, and pricing. Although Chinese and CP feeds are more expensive than local brands, they’re perceived as higher quality. "Local producers believe that making high-quality feed reduces profits. They focus more on quantity than quality," Khan explained.

As demand for floating feeds continues to grow, feed manufacturers are transitioning from pelleted to extruded feeds. Extruded feeds now make up 75% of floating feeds, up from 50% in 2020. Most producers use twin-screw extruders and are shifting from continuous coaters to vertical coaters, with a few even adopting vacuum coating technology.

However, producing floating, extruded feeds is energy-intensive, and energy availability is a major challenge in Bangladesh. Power supply is inconsistent, and oil and gas are mostly imported, adding to production costs and risks.

Despite the country’s large population, a shortage of qualified manpower remains a key obstacle. Bangladesh needs more skilled and technically trained workers to operate and manage feed mills. “A few years ago, there was some technical knowledge sharing, but it was outdated. Recently, USSEC launched training programs such as the Soy Excellence Center, which has been very effective, but not enough,” said Khan.

Another barrier for Bangladeshi feed manufacturers is access to investment. High bank interest rates, ranging from 12% to 16%, make it difficult to secure credit or finance new feed mills. “That’s much higher than what Chinese companies receive from their domestic banks to establish feed mills here, putting local companies at a disadvantage,” Khan noted.

Raw materials

Most raw materials used in Bangladesh are imported. Rice meal is produced locally; however, farmers have recently started shifting toward corn cultivation. Currently, 70-80% of corn is produced domestically, primarily for the poultry industry. “Corn farmers are getting good prices from the animal feed sector, and their production costs are lower because corn requires less labor and irrigation,” Khan said.

In 2019, the Bangladeshi government banned the import of meat and bone meal due to health concerns. This led to an increased reliance on soybean meal, primarily imported from the U.S. “Before 2015, soybean meal inclusion in aquafeeds ranged from 0-15%. In 2024, following the meat and bone meal ban, inclusion levels of soybean meal and soy-based products have risen to as much as 50%,” Khan reported. Soybean oil is also being used more frequently, along with soy lecithin, which has recently been introduced.

In 2024, Bangladesh imported over 3.2 million metric tons of soybeans and soybean meal from the U.S., Brazil, and Argentina. “In Bangladesh, soybeans are either imported as soybean meal or whole beans, which are then crushed by efficient local companies. However, traceability is often a concern. We prefer using U.S. soy to ensure consistent quality and supply,” said Khan.

Khan shared the results of a trial conducted during the grow-out phase of tilapia, comparing soybean meal sourced from the U.S., Brazil, and India. The study found that average daily growth and specific growth rate (SGR) were highest in feeds containing U.S. soybean meal, and lowest in feeds with Indian soy. “Feed conversion ratio (FCR) and survival rates were better with U.S. soy and worse with Indian soy, mainly due to an inferior amino acid profile, high fiber content, and the presence of sand and silica in the Indian product,” Khan said.

Before the 2019 ban on meat and bone meal, major protein sources included dried fish, rapeseed meal from India, and canola meal from Canada. “The quality of Indian rapeseed meal is poor, with high silica and fiber content. It not only affects feed and fish performance but also damages our valuable machinery, like screws,” Khan explained. “These ingredients were mainly used in sinking feeds, which generally result in lower performance and higher pollution in aquaculture water bodies. Luckily, the industry has been moving to other ingredients.”

Fishmeal and fish oil are also used, though at low inclusion rates due to their high cost. Fishmeal is primarily sourced from the Maldives and Oman, while fish oil is imported from Chile and Norway. Vitamins, minerals, and amino acids are imported from China and customized by local pharmaceutical companies.

Diversifying the industry

Bangladesh also produces shrimp, mainly Penaeus monodon and freshwater prawn. In 2022, the country approved the farming of Litopenaeus vannamei, primarily for export markets; however, local shrimp feed production remains low. “Most companies import the same feed from India. Last year, CP established a factory in Bangladesh, but it only produces pelleted feeds,” Khan said. “The fish feed market is well established in Bangladesh, but currently, no one is taking the risk to produce shrimp feeds.”

Carnivorous species are also being promoted by the government. “The government is encouraging the industry to produce barramundi for export markets, but it requires high-quality feed. They’re running a pilot project and importing feed from Thailand,” Khan said.

In Bangladesh, feed companies currently lack the equipment to produce high-quality feeds for carnivorous species like seabass. “Feeds for carnivorous species require low starch levels. But without the right equipment, you can’t float feed with low starch content. To do this, feed companies need to invest in advanced processing equipment. Even Chinese companies are hesitant to produce feeds for carnivorous species because the market is still very small. However, I believe this challenge will be resolved soon. Once we have a reliable power supply, we’ll be able to manufacture feed for carnivorous species,” Khan explained.

Looking ahead

“Our water is excellent, our land is very fertile, but we have limited space and a growing population. Every year, about 1% of agricultural land is lost to housing, and another 1-2% to industry. To meet the rising demand for fish, we must transition to high-density, high-tech aquaculture systems like In-Pond Raceway Systems (IPRS) and Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS), which require skilled labor, consistent power, and low-interest investment,” Khan said. “Systems like in-pond raceway systems promoted by USSEC are well-suited for tilapia production, but we need to ensure high-quality feed and proper conditions to support more advanced farming practices.”

Despite the current challenges, Khan remains optimistic. “If the economy stays on track, aquaculture production could reach 4 million metric tons within the next 10 years.”