With wild fish catches stagnating, aquaculture now supplies most of the world’s seafood, and feed remains its toughest challenge. Kevin Fitzsimmons, Professor at the University of Arizona and co-founder of the F3 Challenge, shares his perspective on the rise of alternative proteins and the future of sustainable seafood.

AQ: You’ve had a long and influential career in aquaculture. What first drew you to this field, and how has your perspective on its role in global food systems evolved?

KF: As an undergraduate, I was taking a marine biology course, and the professor was lecturing about marine fisheries. He pointed out that marine fisheries were the last commercial hunting and gathering profession in the world. For every other kind of food, we had domesticated plants and animals. He pointed out that aquaculture was going to be a growth industry as we domesticated aquatic animals and seaweeds (algae). He described the Tragedy of the Commons and how overfishing, pollution, and gentrification of fishing ports were going to make wild-caught seafood increasingly rare and expensive.

Over time, he was proven completely correct, with climate change, marine plastics, over-subsidized fisheries, competition from sport fishing, and the danger inherent in the “Deadliest Catch – Perfect Storm” profession thrown in for good measure.

Today, aquaculture provides well over half of all seafood, while wild catches have stagnated for 40 years. The percentage supplied by domesticated stocks continues to rise a percentage or two every year.

AQ: Feed remains one of the most critical and controversial aspects of aquaculture. In your view, what are the most pressing challenges the feed industry needs to solve today?

KF: The supplies of fishmeal and fish oil continue to constitute the most expensive portion of many aquaculture diets. Meanwhile, the supplies of fishmeal and fish oil are stagnant or declining globally. Many forage fish stocks are overfished and rife with illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing, not to mention many of the forced and unpaid labor practices reported in certain fisheries. We are also seeing pressure to leave more forage fish in the ocean for cetaceans, seabirds and larger predatory fish. These were never calculated before in the Maximum Sustainable Yield measures, which are purely economic figures.

AQ: What regional differences do you see in the adoption of sustainable feed practices and what can different markets learn from each other?

KF: On a regional basis, the EU and Norway are probably leading the way with the adoption of sustainable feed practices. The salmonids and seabass-seabream feed sectors are being the most affected, as the amount of fishmeal and fish oil is still considerable. Most of the commercial diets have significantly reduced the amount of FM-FO used in favor of more sustainable and less costly ingredients. As the industry continues to grow, the absolute amount of FM-FO used to produce an increasing number of aquatic animals has not increased.

Less developed regions can learn several other lessons. First, there are plenty of alternative ingredients that can provide the needed nutrients. There is no such thing as an essential ingredient; only crucial nutrients that can come from many sources, precisely the same as in human diets. Second, while subsidizing commercial fishing fleets to gather forage fish may be a short-term fix to improve supplies, in the long term, it never reduces the cost of the FM-FO and inevitably leads to overfishing. Third, fishing down the food chain to collect small fish of all species leads to decreases in the capture of large edible fish preferred by consumers.

AQ: Alternative proteins and novel ingredients have gained momentum. How do you see their role evolving in mainstream aquafeeds over the next decade?

KF: These novel ingredients and alternative proteins will continue to accelerate their momentum and take more and more market share. Additional markets in pet food and poultry farming are also jumping on this bandwagon and will increase demand and investment. As the entire world economy focuses more on edible crops for human use and alternatives for animal feeds, we will see huge increases in demand for algae and insect meals, single-cell proteins and fermented and enzymatically treated crop byproducts.

AQ: You’ve been a leading force behind the F3 Challenge. What results or innovations have most surprised or impressed you so far?

KF: We are amazed that what we first proposed 10 years ago has now become the mainstream approach across the aquafeed industry. Some notable success stories include Veramaris and Corbion in the oil category, Protix and other insect meal companies, as well as several single-cell protein producers. Another category that receives little attention is that of companies upscaling waste streams and byproducts into more valuable ingredients. Brewery and distilling byproducts, distillers dried grains with solubles (DDGS), as well as fermented soy, corn, peas, and other grains and legumes, are taking more market share.

F3 2024 Meeting. Credits: F3 Challenge

AQ: Do you think the F3 Challenge has influenced broader industry or policy shifts? How do you measure its impact?

KF: While we were in the vanguard of promoting alternatives with challenges and engagement with the environmental NGO’s, pointing out the problems with the marine ingredients industry, many more have now realized the urgent need for economic, environmental and social changes. We are pleased that the conversations now include alternatives to limited wild-caught marine ingredients and not just complaints about the rapidly increasing costs of those ingredients.

We like to measure the impact, first, by tracking the number of forage fish left in the ocean after contestants use fish-free ingredients in our contests. Second, the volume of alternative ingredients in the marketplace and their increasing share of sales over the years. The number of peer-reviewed science articles and alternative feeds presentations at professional meetings is another key metric.

AQ: What can you tell us about the next F3 Challenge?

KF: The next challenge will be directed more towards individual farmers rather than the big feed companies. The challenge will be based on individual farm sales of fish grown on marine animal ingredient-free diets. Registration for the F3 Fish Farm Challenge will open later this month. Until then, those interested can sign up for updates at farm.f3challenge.org.

As in past challenges, we expect that the publicity of participation will be helpful for all the contestants. We will have several categories for large and small producers of different species.

AQ: How do you envision the future of aquafeeds evolving over the next 5-10 years?

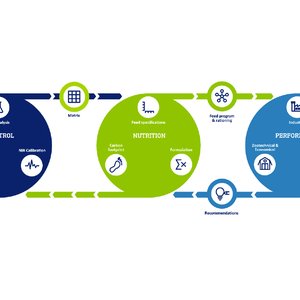

KF: I expect that the marine ingredients will continue their transition from major components to strategic ingredients at smaller and smaller levels of inclusion. The typical formulation for aquafeeds will become more sophisticated with many more ingredients to ensure that all the nutrient demands are satisfied.