In Peru, aquaculture contributes a modest 3% of national production compared to total fisheries output. Extractive fishing represents 97%. Although aquaculture has immense potential, if fully developed, it could position the country as a leader in South America.

Current situation: Species and market

Aquaculture in Peru is marked by contrasts. According to Tulio Merino, manager of the National Aquaculture System (SNA), the sector has two sides: a technology-driven aquaculture aimed at export markets, and a more traditional form linked to self-consumption and regional markets.

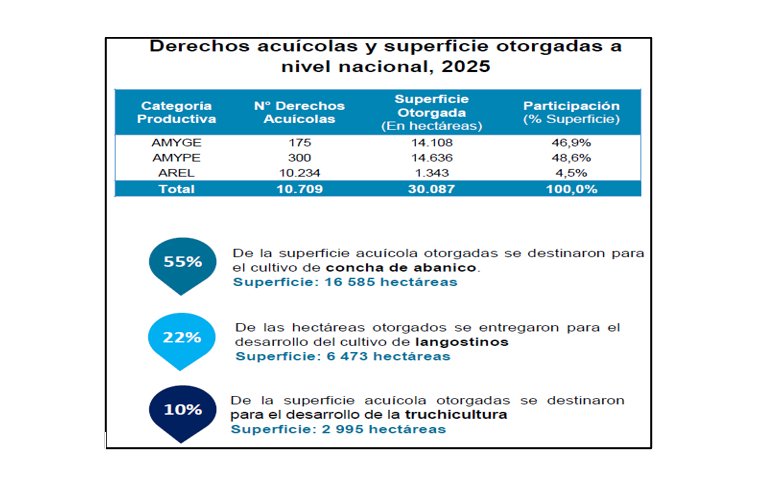

In terms of production categories, 27% of licenses or permits belong to AMYPE (micro and small enterprises) and AMYGE (medium and large enterprises), while 73% correspond to AREL (small-scale aquaculture), focused on subsistence and sales in local or regional markets (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Aquaculture permits and surface area granted nationwide. Source: Ministry of Production

Currently, national production is concentrated mainly on shrimp, trout, and scallops, with tilapia on a smaller scale. In specific regions, Amazonian species such as boquichico, paiche, gamitana, or paco are also farmed, along with Pacific oysters and Malaysian shrimp, though not yet at commercially significant volumes.

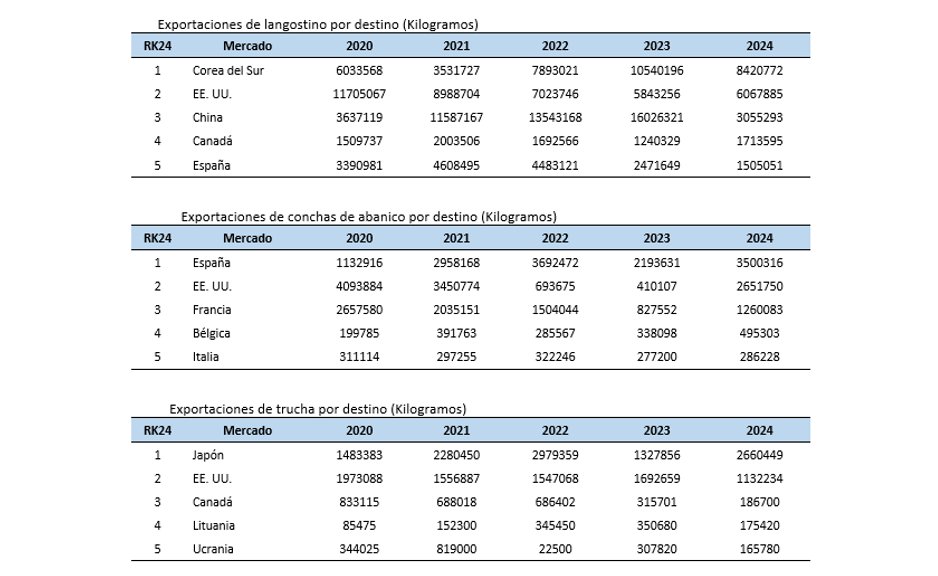

In terms of exports, shrimp and scallops dominate, sending 90-95% of their production abroad. Key destinations for shrimp include South Korea, the United States, and China, while Spain, the United States, and France are main markets for scallops. Trout, on the other hand, is consumed mostly domestically (80%), with Japan, the United States, and Canada as the top export markets (Figure 2). Tilapia is exported mainly to North America.

Figure 2. Export table (kg) by destination. Source: PROMPERU

Decline in production: factors and challenges

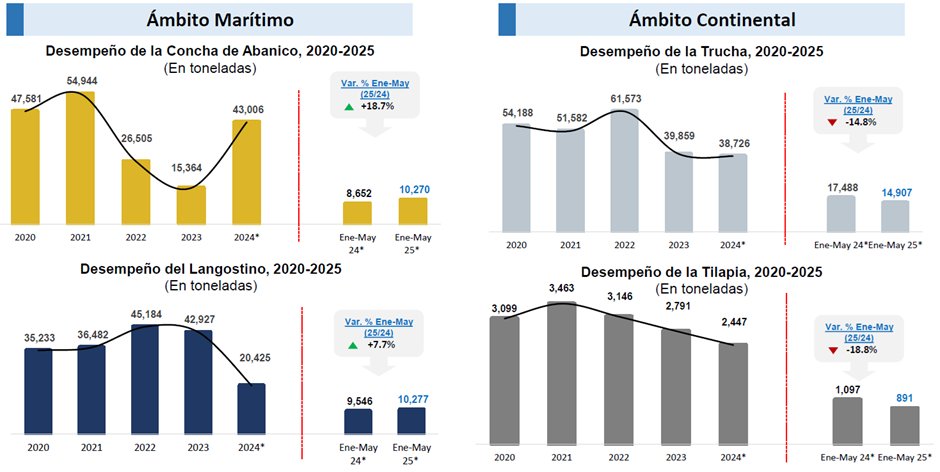

The years 2023 and 2024 saw declines in harvest volumes. Shrimp farming was affected by low international prices and lack of financing, leaving nearly half of the ponds unstocked. In scallops, environmental factors, such as runoff from rivers and streams that altered marine conditions, caused high mortalities. Trout farming suffered from reduced rainfall in the Peruvian highlands, limiting water availability.

Although marine conditions in 2024 allowed a partial recovery in scallop farming, harvest levels have yet to rebound significantly. For 2025, growth of only 8-10% is expected compared to the previous year, mainly due to recovery in the scallop sector and, to a lesser extent, shrimp (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Production of the main aquaculture species. Source: Ministry of Production of Peru

In terms of opportunities, the most consolidated producers have clear strengths: traceability, regulatory compliance, technological innovation, and market diversification. Many operate with vertical integration, from seed labs to processing plants, and comply with international food safety and quality standards. This positions them well in demanding markets and enables progress toward sustainability certifications that open access to more competitive prices.

However, the challenges are substantial. High feed costs, dependence on post-larvae and juveniles, the need to strengthen biosecurity, and limited capacity for collective organization all undermine competitiveness. Added to this are volatile international prices and the challenge of incorporating more value-added products, as most exports are still marketed as commodities.

Opportunities and support policies

Against this backdrop, Peruvian aquaculture still has untapped comparative advantages. The country has species with great potential, such as paiche, tilapia, sole, and Pacific oyster. However, scaling production requires better access infrastructure, reliable energy supply, high-quality seed, and streamlined regulations.

Financing is a key factor. Several medium and large companies access private banking, supported by credit history, collateral, and risk assessments. However, this path remains out of reach for most small-scale farmers, who require tailored schemes.

Public programs that channel targeted resources stand out:

- AREL and AMYPE: funds up to 135,000 soles (USD 38,000) per farmer, mainly in inputs (feed), with an annual interest rate of 7% and a six-month grace period.

- Sechura Bay (scallops): special loans up to 500,000 soles (USD 140,000) individually, or up to 1.5 million soles (USD 423,000) in associations, with preferential rates of 3% and terms up to 20 months.

- Innovation and technology transfer: programs such as Proinnovate and Procompite finance up to 80% of non-reimbursable projects through co-financing schemes.

While limited in scope, these financial tools provide critical support for small producers’ continuity and, in the case of competitive funds, a pathway to accelerate innovation across the value chain.

On the policy front, Law No. 31666 on Aquaculture Promotion and Strengthening provides tax benefits through 2032. It introduces incentives to make aquaculture investment attractive, including reduced income tax, accelerated depreciation, and VAT recovery on operations.

Research also plays a key role. Institutions such as FONDEPES, IMARPE, and aquaculture CITEs lead studies and technology transfer initiatives focused on diversification and sustainability. However, Tulio Merino cautions: “Efforts must focus not only on farming conditions but also on the commercial acceptance and profitability of species.”

Looking ahead

Today, aquaculture accounts for only 3% of Peru’s domestic supply of aquatic resources, well below the global average. This represents both a challenge and an opportunity. “Aquaculture is key to food security and must be seen as a scalable business sector, not just subsistence,” says Merino.

The outlook in export markets is challenging. In the U.S., tariffs on Peruvian aquaculture products are not yet fully defined. Currently, a base tariff of 10% is applied, lower than what Asian and South American competitors face. According to Merino, combined with FTA benefits, this puts Peru in a relatively favorable position: “Buyers will prefer imports from countries with lower tariffs, and this opens an opportunity if we know how to capitalize on it with quality and competitiveness.”

Looking forward, Merino argues that real state involvement is required, with measurable and sustained impact programs, budgets focused on research, technological innovation, and best practices. He stresses the importance of ensuring legal certainty, so investments can rely on a stable and supportive framework, rather than a sanction-based approach rooted in assumptions rather than evidence.

A key aspect is to design differentiated policies: on the one hand, attract large-scale private investment; on the other, establish programs that enable small-scale aquaculture to scale up sustainably, moving beyond temporary aid schemes.

Merino’s vision is clear: the future of Peruvian aquaculture depends on its ability to consolidate as a sustainable, innovative, and competitive business. “Aquaculture is not a low-cost activity, but it is one of high potential. State subsidies may be necessary at an early stage, but they must not be permanent: sustainability will come from research, innovation, and business discipline,” he states.

He concludes: “Aquaculture can become a true driver of sustainable development for Peru if we understand that the goal is not only to produce more, but to produce better.”