At FARM 2025 in Jakarta on September 25, Albert Tacon, a consultant at Suri Tani Pemuka, the aquaculture arm of Japfa Comfeed Indonesia, shared his vision for a stronger shrimp industry. He reminded that feed is the biggest cost for farmers and often relies on imported ingredients. By focusing on water quality, better feed practices, and smarter use of local resources, Albert urged farmers and companies to work together for a more sustainable and secure future.

Feed is the single largest cost in shrimp and fish farming. In many parts of Asia, including Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Thailand, between 50% and 60% of total operating expenses are attributed to feed. Yet, most of the ingredients for that feed are imported. In Indonesia alone, the percentage reaches between 75% and 95%. That dependency on imports makes the industry vulnerable. Prices of soybean, corn, and fishmeal fluctuate in ways that no farmer can control, while the selling price of shrimp often drops. This mismatch threatens farmers’ survival and makes efficient feed management a matter of life and death for their businesses.

Albert said that the role of feed companies extends beyond producing pellets. They must also support farmers in managing feed effectively because only then can real results be achieved. Farmers are the ones paying for the services, and technical guidance must therefore be part of the package.

Success in feed management

Albert outlined what he considered the seven crucial factors for success in feed. At the very top of the list was water quality and water management. He explained with a simple yet striking analogy. Just as people feel drowsy after eating because blood flows to the digestive system, shrimp also need oxygen to digest their food. If oxygen levels in the water are too low, feed passes through undigested, and feed conversion ratios rise. For Albert, dissolved oxygen was even more critical than the feed itself. Four parts per million was acceptable, five was even better, and to reach that level, farms would need more advanced aeration than paddle wheels alone.

The second factor was the production system. Farmers make choices about stocking density and pond type, whether extensive, semi-intensive, or intensive, and these decisions determine how natural food is available to shrimp. Albert shared examples from Mexico and Brazil, where large ponds required trucks for feeding and where continuous feeding practices were common. He noted that the future of aquaculture will lean toward indoor systems, just as livestock and poultry are already raised indoors, because biosecurity cannot be compromised.

Figure 1. Feed transportation & on-farm storage. Credits: Albert Tacon

Other factors included feed formulation and nutrient balance, the method of feed manufacturing, whether pelleted or extruded, and the importance of storage and transportation. He warned that leaving bags of feed outside exposed to humidity was as careless as leaving food for one’s children under the sun. Mycotoxins and fungi thrive in such conditions and can quickly damage valuable feed.

Perhaps one of the most powerful insights was about people. On most farms, the ones responsible for feeding shrimp are often those with the lowest salaries. Yet, in Albert’s words, they are the most important workers. Their judgment, discipline, and consistency shape the success of feed management. "Ultimately, what truly matters is the performance of the feed," he explained.

More secure and inclusive aquaculture

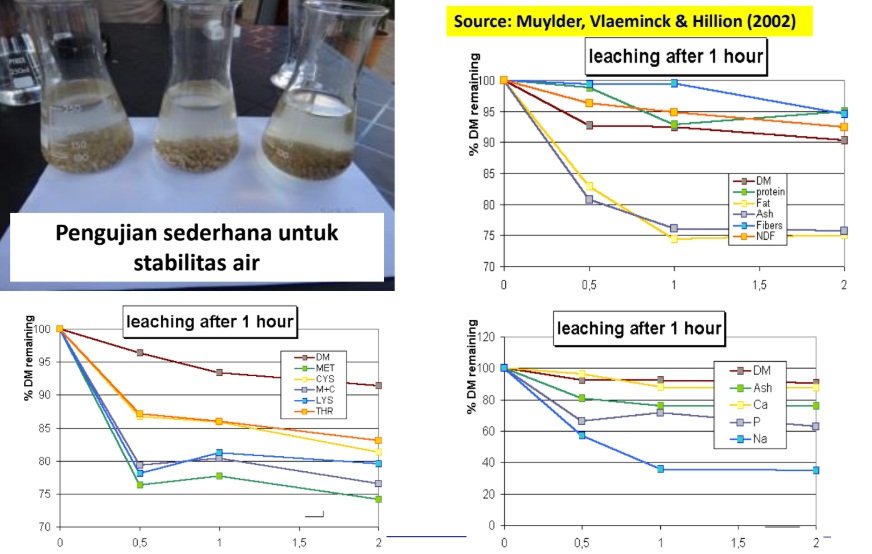

Albert devoted significant time to the science behind feed. He spoke about leaching, the process by which nutrients dissolve into water as the longer pellets remain uneaten. Twenty-five essential nutrients, including amino acids, are water-soluble, and once they leach, they are lost to the shrimp. Temperature, salinity, and particle size all influence the rate at which this process occurs. This is why feeding frequency and methods matter. Shrimp do not eat three or four times a day like humans. They graze continuously. For Albert, automation and controlled feeding systems are part of the future; yet, the most immediate step is maintaining high oxygen levels so that shrimp can digest what they consume.

Figure 2. Simple test for water stability. Credits: Albert Tacon

Looking ahead, Albert encouraged Indonesia to explore more local ingredients. Palm kernel and copra meal may not appear promising at first due to their high fiber and low protein content, but fermentation technologies developed in Bogor and elsewhere could unlock their potential. Reducing reliance on imported soy and corn would improve resilience.

Albert also emphasized that aquaculture should be part of the solution to poverty. Indonesia has a population of more than 283 million, with 60% of its citizens living near or below the poverty line. By developing a stronger domestic shrimp market, as seen in Brazil, where smaller shrimp sizes are sold locally at better prices, farmers can diversify beyond export markets. This approach not only secures livelihoods but also makes shrimp more accessible to local consumers.

As Albert concluded his presentation, he said that feed is more than a cost item. It is the central pillar of sustainable aquaculture. Its management requires science, technology, and above all, collaboration between feed companies and farmers. By working together and valuing the people at every step of the chain, the industry can withstand global price shocks, secure its future, and bring prosperity to those who depend on it.